Photography, motion pictures and stereography evolved simultaneously and many devices of optical wonder were created that conferred movement, depth and color on images with both simple and complex means. Even prior to the invention of photography the peep show and magic lantern were popular optical entertainments in which various showmen ingeniously incorporated depth and movement.

devices of optical wonder were created that conferred movement, depth and color on images with both simple and complex means. Even prior to the invention of photography the peep show and magic lantern were popular optical entertainments in which various showmen ingeniously incorporated depth and movement.

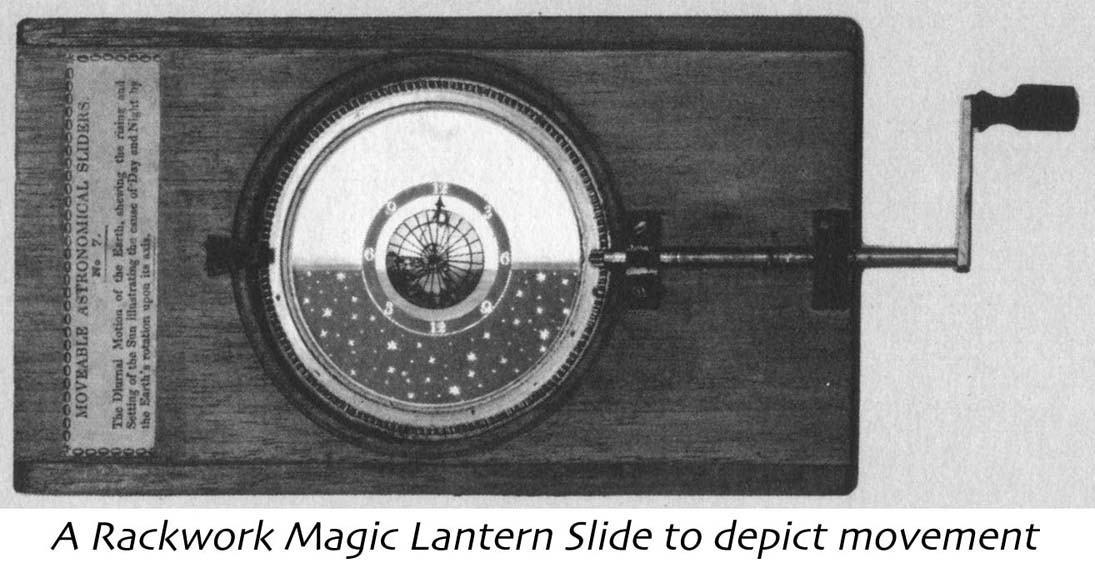

When stereophotography was invented and the market for stereoscopes and stereoviews proliferated, the use of a blinking eye technique alternately opening and closing the left and right eye, was present as a simple means of creating binocular movement of the image. For many years, magic lantern showmen had made use of mechanical slides to animate the projected image. Rackwork slides achieved motion through the action of a rack and pinion that were turned while the slide was projected. There were also pulley slides consisting of two glass discs mounted in brass rings that turned in opposite directions by means of two bands and projected patterns of brilliant color or moving shadows.

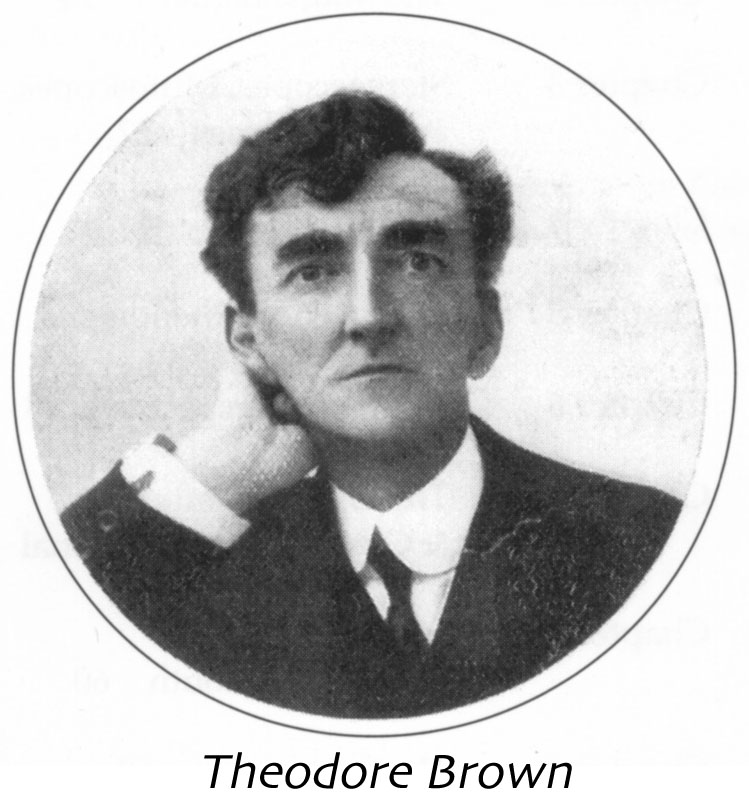

Theodore Brown was a prolific inventor of optical entertainments who was active at the turn of the 19th century and made many experiments with early motion pictures, stereoscopic photography and an anaglyphic system of moving picture drawings for children that he called Magic Motion Picture Books. Brown was the author of the 1903 book Stereoscopic Phenomena of Light and Sight (reprinted in a facsimile edition by Reel 3-D in 1994) and a mail-order merchant of stereoscopic devices such as a mirror attachment enabling ordinary cameras to take stereophotographs.

Theodore Brown was a prolific inventor of optical entertainments who was active at the turn of the 19th century and made many experiments with early motion pictures, stereoscopic photography and an anaglyphic system of moving picture drawings for children that he called Magic Motion Picture Books. Brown was the author of the 1903 book Stereoscopic Phenomena of Light and Sight (reprinted in a facsimile edition by Reel 3-D in 1994) and a mail-order merchant of stereoscopic devices such as a mirror attachment enabling ordinary cameras to take stereophotographs.

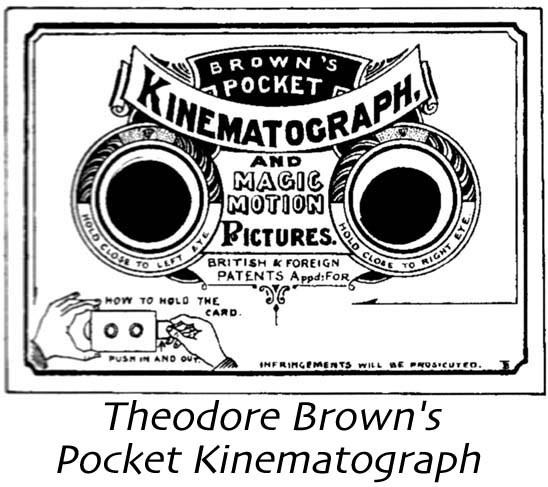

Brown first published red/green stereographs which he called Magic Post Cards using anaglyph glasses that were attached in 1904. By 1908, Brown had developed the Pocket Kinematograph, producing Magic Motion in anaglyph pictures by sliding the red and green lenses back and forth in a cardboard sleeve. Brown subsequently published numerous children’s books which used green and red filters to create motion with titles such as the Book of Moving Pictures, Children?s Encyclopedia and The Cinema Book.

A stereo polymath of the first rank, Brown also developed a stereoscopic application of Pepper’s Ghost for live performance, motional perspective which was a monocular application of the Pulfrich effect years prior to its discovery in 1922, and, for his whole life, worked to perfect an autostereoscopic motion picture process he called Direct Stereoscopic Projection. At the end of his life and up to his death in 1930, Brown achieved great success as a paper engineer for clever Pop-Up Books.

application of the Pulfrich effect years prior to its discovery in 1922, and, for his whole life, worked to perfect an autostereoscopic motion picture process he called Direct Stereoscopic Projection. At the end of his life and up to his death in 1930, Brown achieved great success as a paper engineer for clever Pop-Up Books.

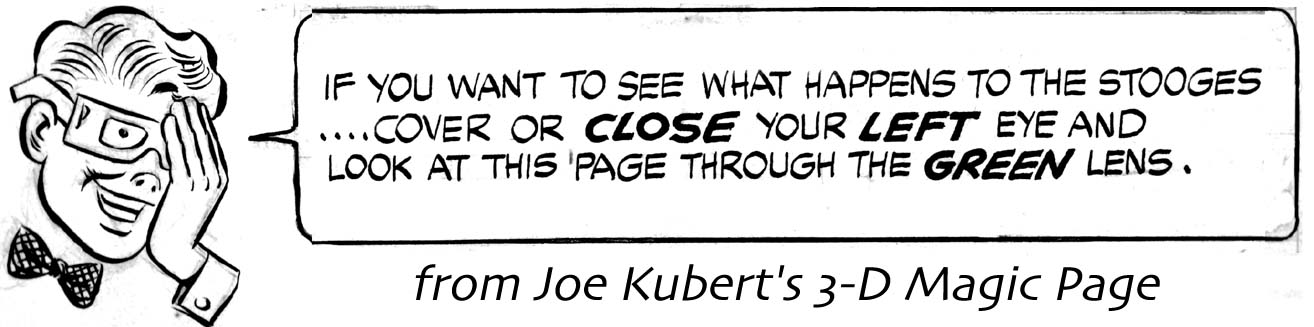

The anaglyphic blinker has survived to the present day. In 1953 Joe Kubert and Norman Maurer used it for 3-D Magic pages in the St. John 3-D Comics. A humorous example from The Three Dimension 3 Stooges instructs the reader to view the page from the RED lens only. The view through the GREEN lens reveals a clever twist to the gag that has been set up through the red lens. Other St. John 3-D Magic pages such as The Story of Evolution in 3-D Tor by Joe Kubert revealed what happened to the Wooly Mammoth after millions of years of evolution.

Harvey 3D Comics also used the technique in 1953 for one page Three D Blinkey stories which featured two different endings viewable through either the red or green lens of the anaglyph glasses. This technique was also used for a 1922 anaglyphic feature film produced by Harry K. Fairall called The Power of Love that premiered at The Ambassador Theater in Los Angeles. The last reel of The Power of Love could be viewed through either the red or green lens depending on which ending the viewer wanted to witness, happy or tragic.

There have been other more recent examples of the anaglyphic motion blinker in publication with the Normalman 3-D Annual #1 (Renegade Press: 1986), 3-Dementia Comics, (3-D Zone: 1987), The Alf Stickerbook (Diamond Publishing: 1987) which included a Slide-O-Scope Movie Viewer and a one-shot issue of The Flintstones comic book in the 1990s.

Theodore Brown’s Pocket Kinematograph made reading an interactive experience years before the concept even existed. 19th century stereographic pioneers foreshadowed in many different ways the multi-media of the 21st century.

References:

Brown, Theodore. Stereoscopic Phenomena of Light & Sight (facsimile of 1903 edition). Reel 3-D Enterprises, Inc. 1994.

Ceram, C.W. Archaeology of the Cinema. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc. (no date).

Herbert, Stephen. Theodore Brown’s Magic Pictures, The Art and Inventions of a Multi-Media Pioneer. London: The Projection Box. 1997.